After telling us to “Bear one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ”, the apostle Paul states plainly in Galatians 6:7

“Do not be deceived: God is not mocked, for whatever one sows that will he also reap.”

And as I consider the recent events in the USA regarding Michael Brown and Eric Garner, for the first time today I read those words from Paul and connected them with Moses’ words in Exodus 20:5, that speak of God “visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation …”

I’m not interested in armchair-lawyering the justice (or lack of justice) that resulted from the criminal investigations that followed both these incidents. I’m also not interested in trying to speculate or prove that these deaths were racially motivated; the ones that ultimately know the real answer to that question are Darren Wilson, Daniel Pantaleo and God alone.

What interests me here is a deeper question behind the questions of excessive force, choke holds, and the effectiveness of the justice system: a question of origins.

A case study

We’ve become all too familiar with terrible stories about the cycle of domestic abuse and the women/children who are trapped in them. It’s heartbreaking to hear about and, undoubtedly devastating to live through. And looking from the outside, as we see these battered and abused women continuing to stay in these destructive relationships, we often ask ourselves “Why don’t they just leave?” or “Why would they continue to tolerate such behaviour?”

But if you think about the origins of this cycle of abuse, it’s no stretch of the imagination to believe that no boyfriend or husband starts out beating up on/being physically violent with his partner, on the first date. Likely, a relationship, or a deeper bond of some kind, is built first before any abusive behaviour really starts to materialize. And once that relationship has been established – even in spite of the physical and mental violence inflicted – it becomes incredibly hard to break free and rise above such circumstances. And once the woman is freed from that abusive relationship, she often still experiences the trauma/anxiety of it, even when her new relationship now poses none of the same threat.

The case study flipped and re-applied

My question is: what if someone did start out with abusive behaviour (under which the oppressed person could not get out from under) and then – over time – gradually reduced the abusive behaviour and finally began to act favourably towards the person? The order of the cycle of abuse has been reversed, yes, but I wonder the effect is not the exact same on the abused person.

-

The statistics are clear in my view (see pg. 5 from a US research project regarding African Americans in the penal system – image below).

(http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_Trends_in_Corrections_Fact_sheet.pdf)

Or see this post from Reuters in Canada regarding First Nations peoples in our penal system.

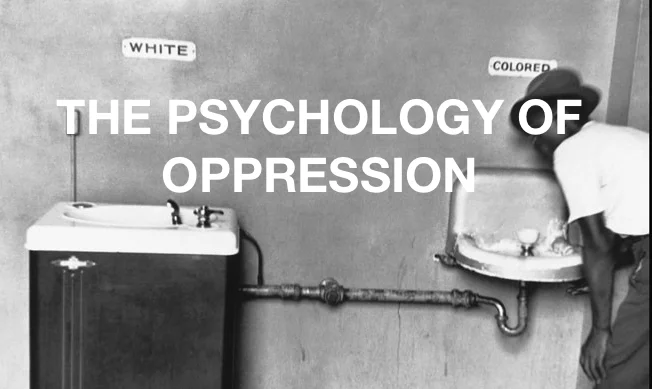

Even if all the history you know of the settlement of America and Canada is from films like “Amistad” and “Last of the Mohicans”, you know, at least, that the hands of our ancestors are stained with a great deal of the blood of both the African American and First Nations peoples.

-

Tadeusz Grygier, a doctor of social and criminal psychology wrote in his recent work, “Oppression: a study of social and criminal psychology” which drew from his own experience in Soviet war camps as well as research done with survivors of Nazi concentration camps, found these startling conclusions about the psychology of oppressed people:

- oppression tends to produce an extrapunitive attitude in the oppressed, diverting aggression to external persons and situations

- it leads to psychopathy and crime

- more severe degrees of oppression greatly increase the incidence of crime

(see: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2079301/pdf/brmedj03620-0049c.pdf)

Testing the hypothesis

It’s doesn’t explain everything by a long shot. But if you look at the justice system’s statistics of formerly (some would say still currently) oppressed people groups, and place them alongside Dr. Grygier’s findings, I think it brings up some difficult questions to answer.

It makes me wonder if – although we (as middle class white people anyways) like to say that “racism in C21 is all but dead”, and then base that statement on the fact that the stark horrors of our forefather’s oppression are no longer taking place – it makes me wonder if we’ve really considered the psychology of that former oppression and the effect it still has on future generations? If the “feeling” of oppression and subjugation has not been passed on from those formerly oppressed generations? So that now – although the present threat of domination/subjugation has been quelled – the ability to experience the freedom and non-suspicious life we enjoy today in white North America, still feels out of reach?

It makes me wonder if the sins of our forefathers did not create a present day “oppressed psychology” which is also invisible to our eyes, and which helps to create much of the sociological, economic, and educational disparities we see between ethnicities today, and then the resulting criminal behaviour that can follow out of that oppressed mindset?

And if now we are simply reaping what was sown?